Tananarive Due: Life, Legacy, and all the Horrors Between

- theghoulsnextdoor

- 60 minutes ago

- 15 min read

Tananarive Due seamlessly weaves vivid, realistic characters with powerful historical influences. True blue horror with high body counts, pulling no punches, and yet with immense care and consideration for her readers, Due is a brilliant storyteller.

gabe reviews two of her books, their blend of horror and reality, and how it leaves them wanting more, more, more! Kae shares about Due’s life, family, and long history of activism.

Tananarive Due: Healing Through Horror Fiction

by gabe castro

RED: Quotes, someone else's words.

The Good House

The Good House (2003) is one of the best haunted house stories I’ve ever read. (That's high praise for me, as ‘haunted houses’ is one of my favorite subgenres of horror). Tananarive Due is brilliant when it comes to weaving traditional horror narratives with deeply impactful history, trauma, and triumph. The Good House is a terrifying and intriguing multi-generational haunted house story. It reads like the classic horror staples you may love, akin to King in both the savage approach to death and the insidious, far-reaching nature of evil, infecting the very soil.

Book Summary

In the Good House, Angela returns to her grandmother’s famous home, named Good House, hoping it will save her failing marriage, heal the disconnection between herself and her teenage son, and help her find the answer to her future. Angela’s grandmother was known as a healer, both as a pillar of this town and as being looked down upon for her ancestry and race. Despite her good intentions, the house harbors something far more sinister in store for Angela, her loved ones, and the town of Sakajawea. The first domino is the death of her son, Corey, in their basement during a Fourth of July party.

Two years after this devastating event. Angela returns to Good House in hopes of putting her grief, history, and the home to rest. Since Corey’s passing, many other deaths have plagued the town, a landslide of tragedy that grows more frequent and savage in her return.

She works to link her grandmother’s past, the history of the land, and the activities of her son before his death to the horrors of today, revealing a deep evil thriving on the pain. She works to unravel the tangled web that infected generations of her family.

Book Review

This is the second book I’ve read by Due, and while I was already hooked by The Reformatory, that desire was kicked into high gear after reading The Good House. Due paints a vivid picture of Sacajawea, a land drenched in oppression, hate, and pain that’s desperately trying to distance itself from that history. Each character feels rich and complicated. I was emotionally devastated by nearly every death. Each one felt unfair and brutal, the true nature of death we don’t always see in horror novels with such a high body count. As the bodies pile up and readers understand that no one is safe, it feels truly hopeless.

It’s a heftier book, nearly 600 pages, and it takes a bit of time to adjust to the storytelling, letting the plot slowly reveal itself. It’s entirely worth the wait! There’s a slow peppering in of these lives and experiences, bouncing between time and characters.

Due creates vivid, realistic characters that have me in my feelings. Every decision by these characters feels relatable, and while frustrating at times, still believable. There is a heaviness that sits with me in the character of Tyriq, Angela’s ex-husband, who, while deeply flawed, didn’t deserve his fate. What he endures hurts so deeply when you remember the work he’s done to be better, to grow as a person, and make do with the life he’s found himself in.

Angela’s teenage boy, Corey, is believable in his snobby youth. He is learning to navigate his future, his feelings, his growing body, and the complicated relationship with his parents. Showing much of his life through the eyes of his mother and those around him, we’re forced to form his image with scraps. Just like a teenager to be terribly misunderstood. His truth, later revealed through his own experiences, hurts even more knowing how he ends up.

Angela herself is a complicated woman, both fleeing to and from her past. She holds firmly onto the strength and notoriety of her grandmother while ignoring and suppressing the reality of her mother. She acknowledges and delights in her grandmother’s superstitions and power while also dismissing their truth.

Even the side characters, whom we meet in passing or on the worst day of their lives, are vivid and emotional. No one is painted in one shade, no one is evil or good; they simply are. This is the strength of Due’s The Good House, even amidst the supernatural and magical horrors of this world, there is loud and unapologetic truth in each person affected. It’s a truly gripping horror novel, and if you’ve ever read a Stephen King, I promise you’ll love this even more.

The Reformatory

The Reformatory (2023) is a heartbreaking, gripping horror novel where the only thing more terrifying than the horrors on the page are the real ones that inspired it. The Reformatory is a historical fiction horror novel with supernatural elements woven within.

Book Summary

Set during Jim Crow in Florida, The Reformatory follows Robert Stephens Jr after he’s sent to a reform school, well known even at the time for being a death sentence of horrors, racism, and injustice.

Due introduces us to siblings Robbie Stephens and his older sister, Gloria, as they try to navigate the complicated world as glorified orphans, their father off fighting for freedom elsewhere. After trying to defend his sister’s honor, twelve-year-old Robbie is sent to the Gracetown School for Boys. He is met with the horrors of both the living and the dead. This crooked, corrupt system delights in the abuse and harm of these wayward boys, and Robbie gets dropped into the middle of two worlds. Robbie can see haints (or ghosts) and finds himself overwhelmed by the presence of them in this place, rich in pain and suffering.

He finds friendship with Blue and Redbone, who help him navigate the paths of this new world while trying to stomach the reality behind the haints. Gloria fights like hell on the outside to save her brother, doing everything she can to save him from the tragic fate he seems destined for.

Book Review

After the death of her mother, Due received word that her Uncle, Robert Stephens, was most likely buried on the grounds of a real-life nightmare, the Dozier School for Boys. This reform school was the site of abuse and scandal, covered up and denied for years. After receiving this news, learning for the first time about not only the tragic death of this relative but also of his existence, Due sought to uncover the full truth of his life. She traveled to the small panhandle town in Florida, where the school had been. Due shared her thoughts on the visit, “It was really almost as if history was trapped at that site. I couldn't imagine what it would be like to be a child at this hell house.”

Moved by the heaviness she felt in the space, she sought to share the history with others, while being mindful of the pain resurrecting this history could invoke on the generations still affected by the losses. Due spent 7 long years navigating the history of the school, uncovering her uncle’s experiences, and crafting a narrative for her fictional Robert Stephens to find retribution. “When we’re writing about difficult times in history, the line between trauma porn and honoring the past can be very thin,” shared Due. While conscious of this delicate balance, Due holds no punches.

Death looms over the characters, and through Robbie’s sixth sense, we’re able to experience the horrors from a distance as they replay from the past. It’s a heavy story that you won’t be able to put down, desperate to see these siblings united and healthy, but also to see the end of this corrupt place.

Through Robbie’s story, we’re offered an alternative world where Due’s Uncle Robert is saved, his life no longer buried as a dark secret, and instead, the truth behind his suffering is brought into the light. Readers get an insider glimpse into the system set on utilizing and abusing Black bodies, and impoverished white ones, too. Robbie’s Jewish social worker says as much, “That place pays the county a good sum for every boy sent there, so you’ve just been sold. Never forget that. They don’t want to send you home.”

Through Gloria’s side of the story, Due reveals a society and system that makes something as horrifying as the Reformatory possible. Gloria fights against the legal system, intent on putting an innocent, sweet boy away for standing against the status quo. The McCormacks, the family responsible for Robbie’s institutionalization, have a history of benefitting from injustice, the slavery of the past, and the book’s present, Jim Crow.

Due’s Gracetown is rich with historical truths; nothing exists without meaning. Queer characters, the Klan, lynching trees, Jewish social workers, segregated fishing spots, their father’s flight to Chicago, union-busting, and more. Due did her due diligence, and while this was the longest she’d ever worked on a book, each piece of research was worth it. The Reformatory and Gracetown are both vivid representations of a toxic, insidious American history that’s too easily ignored. As Gloria and Robbie’s guardian explains in the book, “We got a sickness here in Gracetown, Gloria. Maybe at the Reformatory, worst of all. […] A blood sickness. Too much killing and dying. Too many restless spirits. Angry spirits. […] Maybe it’s a curse on us—a town named for Grace that don’t act like no godly place.”

Looking back on the history that inspired this thinly-veiled fictional novel, we can admit that America is one such ungodly place. Stories like this one, crafted in a digestible, thought-provoking way and with the immense care and consideration of Due, are one step towards reparations.

The Reformatory and The Good House are invitations from Due. Asking us to open the doors to the past, to look them in the eye so we can confront the horrors that have been rooted in our soil all this time, festering and feeding off the pain of our history. Only once we’ve faced those truths can we move forward towards healing.

Tananarive Due: A Lifetime of Activism & Horror Fiction

by Kae Luck

RED: Quotes, someone else's words.

Tananarive Due Bio

Tananarive Due, according to the bio on her website, is an award-winning author who teaches Black Horror and Afrofuturism at UCLA. For more than 20 years, she has been a leading voice in Black Speculative Fiction, and through this work, she’s won an American Book Award, an NAACP Image Award, and a British Fantasy Award. With this, her work has also been included in best-of-the-year Anthologies. She has written many books, two of which we discuss in this episode, including The Reformatory, The Good House, The Wishing Pool and Other Stories, Ghost Summer: Stories, and My Soul to Keep. The Reformatory has won many awards as well, including a Los Angeles Times Book Prize, Chautauqua Prize, Bram Stoker Award, Shirley Jackson Award, World Fantasy Award, and a New York Times Notable Book Award. She has also written a book with her late Mother, Civil Rights Activist Patricia Stephens Due, called Freedom in the Family: A Mother-Daughter Memoir of the Fight for Civil Rights. It’s a really inspiring and educational book, and I’m most of the way through and recommend giving that a read too if you like her fiction titles. It gives you a lot of context for our world and how and why Tananarive writes.

Some additional background on Tananarive Due is that she was an executive producer on Horror Noire: A History of Black Horror, which was created on Shudder, and I believe we’ve mentioned it before on our show because it does what we’ve always wanted to do, and showcases the impact of horror and all it can say compared to other genres. Tananarive and her husband Steven Barnes collaborate as well, and wrote “A Small Town” for Season 2 of Jordan Peele’s “The Twilight Zone” on Paramount Plus, and two segments of Shudder’s anthology film Horror Noire. They co-wrote their Black Horror graphic novel, The Keeper, illustrated by Marco Finnegan, AND they have a podcast as we do. She and her husband co-host a podcast together called “Lifewriting: Write for Your Life!”

Life and Legacy

Tananarive Due was born January 5th, 1966, in Tallahassee, Florida. Their birthday was also recently, from when we are recording this episode, so happy belated Birthday! She spent much of her life in Florida, in different areas and looked up to her parents and their activism. In her youth, she was immediately impacted by racism, as her parents tried to find her a Montessori preschool to attend, and were met with White’s only at each attempt. This was post Brown v Board of Education, but private schools did not have to follow the same rules as public ones. When moving to Miami, they ended up in a predominantly White suburban area, where they experienced racism even more from neighbors. Tananarive and her sisters ended up attending a private school called the Horizon School for Gifted Children, at the recommendation of Nancy Adams, a friend of their mother’s from the civil rights movement. Much of her childhood was defined by the impact of her mother on the world. Her mother’s influence granted her connections and access to spaces that most other Black families of the time did not experience.

The impact of being a predominantly white area might have been worse if not for the consistent effort of her parents to educate them outside of school, too. Her mother made sure they knew who they were and about history. Her house was filled with books, and Tananarive loved to read, which, as a writer, makes sense. After an incident at school that made Tananarive come home and question the impact of Martin Luther King Jr. She had come home and said something to the effect of “Martin Luther King was a troublemaker,” and then her mother decided that even if Horizon was a great school academically, the whiteness and isolation of it wasn’t. So they moved to go to public schools, which Tananarive describes in the book as also being isolating, but in a different way. At R. R. Moton Elementary School, she struggled socially because the other kids didn’t like how she spoke. Even teachers gave her a hard time. This is when she really started to become politicized and wrote poetry about the experiences she was facing. She won many awards for her poetry. From this point on, her activism took flight. She became actively involved in the NAACP junior division and accompanied their parents to protests. Their childhood had already been that, inherent to being the child of activists, but the older they got, the more involved they became. She helped call for people to vote, joined her family as they protested, worked with the NAACP, wrote letters, and worked with political officials, and more. So let’s unpack a bit about her parents.

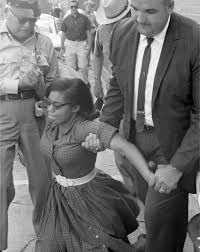

The legacy of Tananarive Due and her family is impactful, to say the least, as both her parents were civil rights activists. Her mother, Patricia Stephens Due, was a part of the student sit-in movement, and was known for leading the landmark first “jail-in” with her sister, Pricilla Stephens. During the sit-in movement, people were often arrested and then would pay a fine for the arrest. Rarely would they serve the 49-day jail sentence, but Patricia Stephens Due, along with her sister, took the jail time as a protest. This ended up being extremely impactful and brought national attention to their movement. The impact of the knowledge that two Black women were arrested and jailed for 49 days because they sat at a lunch counter inspired other activists to fight back. Tananarive’s father, John Dorsey Due Jr., worked with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a civil rights attorney in Saint Augustine, Florida, where Dr. King and hundreds of protestors were arrested. So many big history makers in her family.

I’ll read a little from their book Freedom In the Family in hopes it will inspire you to pick it up and give it a read, but the first page gets right to the point and is inspiring af. Patricia Stephens Due says: “There are so many misconceptions today about the civil rights movement. People think Black people were a unified front in the “old days,” with everyone marching and holding hands. Well, that’s not true. If only it had been that easy! Just like today, in cities and towns across the South, there were always a select few who lit the fires and went to the meetings - and eventually, others followed. Dr. Martin Luther King wasn’t the only one lighting the fires. He had a lot of influence, but he was only one man. It concerns me when I hear people say If only we had Martin Luther King today, as if we are helpless without him.

Her mother, Patricia Stephens Due, was born in 1939 to Lottie Mae Powell and Horace Walter Stephens. Their names might sound familiar if you read The Reformatory. Patricia’s father was run out of town because both white and Black patrons visited his nightclub, and the local white powers would not tolerate “mixing”. He was a chef and a tap dancer. Although Patricia’s parents did not stay together, her mother always spoke highly of his talents. After her parents' divorce, Patricia grew up outside of Quincy, Florida. She lived with her grandmother for a few years with her sister and brother. Her mother remarried, Marian M. Hamilton, apparently from the Hamilton family, as in descendants of Alexander Hamilton. She shares stories of her childhood, dealing with the segregated South.

A line from the book that really hit me, which I think feels especially potent right now, was when Patricia was talking to her mother while sitting in jail. Her mother asked her and her sister if they really wanted to do this, as in to serve the jail sentence, and Patricia responded with: “Mother, if your generation had done this, we wouldn’t have to do it now. It’s time for all of us to be free.” and her mother responded with “well then girls, you have to do what you have to do.” All the work Patricia Stephens Due and John Dorsey Due put in during the Civil Rights Movement paved the way for the world Tananarive and her sisters grew up in. The spaces they were able to occupy that her parents would have been shunned from. Racism was still everywhere, but doors were opened more than in any previous generation. I highly recommend checking out the rest of the book, as it provides a lot of history.

Interview and motivation for writing

Although I hope that one day we’ll have the chance to interview Tananarive Due ourselves, she has been interviewed before, so I’ll be pulling some content from those interviews here and then combining that with some stuff from the book. In an interview on Horror.org titled “Black Heritage in Horror: An Interview with Tananarive Due,” they unpack what inspired Tananarive Due to start writing. She says, “I’ve always been a writer. One of my earliest memories is folding white paper in half, drawing stick figures and captions, and titling the book “Baby Bobby.” On the back, I wrote “Baby Bobby is a book about a baby. The author is Tananarive Due.” I spelled a bunch of the words wrong, but BOOM. I came into this world understanding that I was a writer.”

In the book Freedom in the Family, she also discusses how she came to love writing, in that it was a way to translate her emotions about the injustices in the world, as well as convey them to others. An activist herself, she would often work alongside her mother to fight against offensive representations of Black Culture and oppression. In Chapter Six, she wrote of an experience with a car dealer who painted an offensive mural on the side of his building. This experience didn’t go as she had hoped, and it was her first time arguing against this kind of representation by herself. The man refused to take down the mural, and she left the interaction frustrated. This experience, along with a few others mentioned in the book, taught her something about herself.

She wrote: “By then, I really understood better what my place in life would be. I was not the firebrand who could confront anyone with ease, like my mother I also did not live in the realm of philosophy, sociology, and law, like my father, I was a writer. I could escape through writing. I could teach through writing. I could air shared emotions through writing. I could tell people what had happened- exactly how it happened- through writing. As long as I could write it, people would know.“

The Interview continues, Question: “What was it about the horror genre that drew you to it?”

Due says: My late mother, Patricia Stephens Due, was a civil rights activist who suffered trauma at the hands of police when she was an activist in the 1960s. She was also the first horror fan in my life, which I consider directly related. So many people who have suffered trauma are drawn to horror, and my mother was no exception. So she was always watching horror movies, including the old Universal classics like The Wolf Man, Dracula and The Mole People. She also gave me my first Stephen King novel, The Shining, when I was 16. So King helped me understand that horror could be literary, not just cinematic – and although I hid it for myself for a long time, that was the kind of writing I wanted to do. When I say I hid it, that’s because I didn’t understand until I was out of college that I hadn’t given myself “permission” to write horror as a Black woman.

Question: Do you make a conscious effort to include African diaspora characters and themes in your writing and if so, what do you want to portray?

Due Responds: I would have to say the effort WAS conscious. I got an M.A. in English literature from the University of Leeds in England, and as an international student myself that was the first time I found myself surrounded by African students from Ghana, Nigeria and South Africa. I have to admit that there were times I’d felt outcast in Black circles at home, since I was called “Oreo” in elementary school, and it truly felt like a homecoming to me. I also specialized in Nigerian literature, and I was so inspired by the works of Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe and other writers that I do believe I carried a bit of that experience back with me.

In my first novel, The Between, Dede’s mother is Ghanaian. My Soul To Keep centers Ethiopian immortals. Between my grad school experience and my first name from Madagascar, I’ve always felt a sense of Diasporic kinship. I have no patience for Diaspora Wars.”

Question: What has writing horror taught you about the world and yourself?

Due responds: The biggest thing I’ve learned is that I find the real world much more frightening than anything I can write about in my books. I can’t watch or listen to true crime stories because I’m so appalled by human evil. Writing horror has taught me how to compartmentalize the things I find most scary in life into bite-sized pieces that can help me and my readers get our emotional bearings and keep on going.

I recommend checking the full interview out on horror.org to hear more about her motivations for writing horror.